Legal aspects to keep in mind building IoT solutions

III. Who provides the solution?

Due to the decentralized characteristics of the blockchain technology, the provider of the solution could be in Germany, in Germany and several other countries as well as outside of Germany. Depending on the location of the server nodes of the blockchain on which the Smart Contract of the solution is executed. One could therefore speak of a cross-border association or a cross border company.

Therefore, one of the most business critical questions at the transformation of a data driven business model on Blockchain technologies is always: Who provides the solution?

The answer is not only about reliability. As well – especially in the B2B context – it is about which entity will be the right contract partner to deal with. Who provides the infrastructure and bears the costs? Who maintains the solution? Which local laws apply? Which legal form will the operator of the blockchain solution choose? Where will be the registered office of the provider?

For the future implementation of the operator of a solution on blockchain technology, the applicability of national law for the establishment of the association is problematic and must therefore be clarified. Neither the German Civil Code (EGBGB) nor European law contains a conflict rule for the company statute in international company law.

In German law, the domicile theory applies up to now, i.e. the company is basically included in the legal system applicable at its domicile. German law would then be applicable, if the operator has its registered office in Stuttgart.

In European law as well as in Anglo-American law the foundation theory is predominant. According to this, the legal system according to which the legal entity was founded is applied. German law would only be applicable according to the foundation theory, if the provider would be founded in Germany, e.g. in Stuttgart.

In the search for the appropriate legal form for the business model, the social aspect of the decentralised nature of the block chain should continue to be taken into account. Probably, not every participant of a value chain would like to share its data with a central company outside his sphere of influence. The reasons could be e.g. lack of trust, protections of productions secrets, lack of adequate compensation. As well it would be difficult to run the server infrastructure for the blockchain nodes within the data centers of the participating companies out of a central concept if e.g. a consortium chain has been chosen as technology.

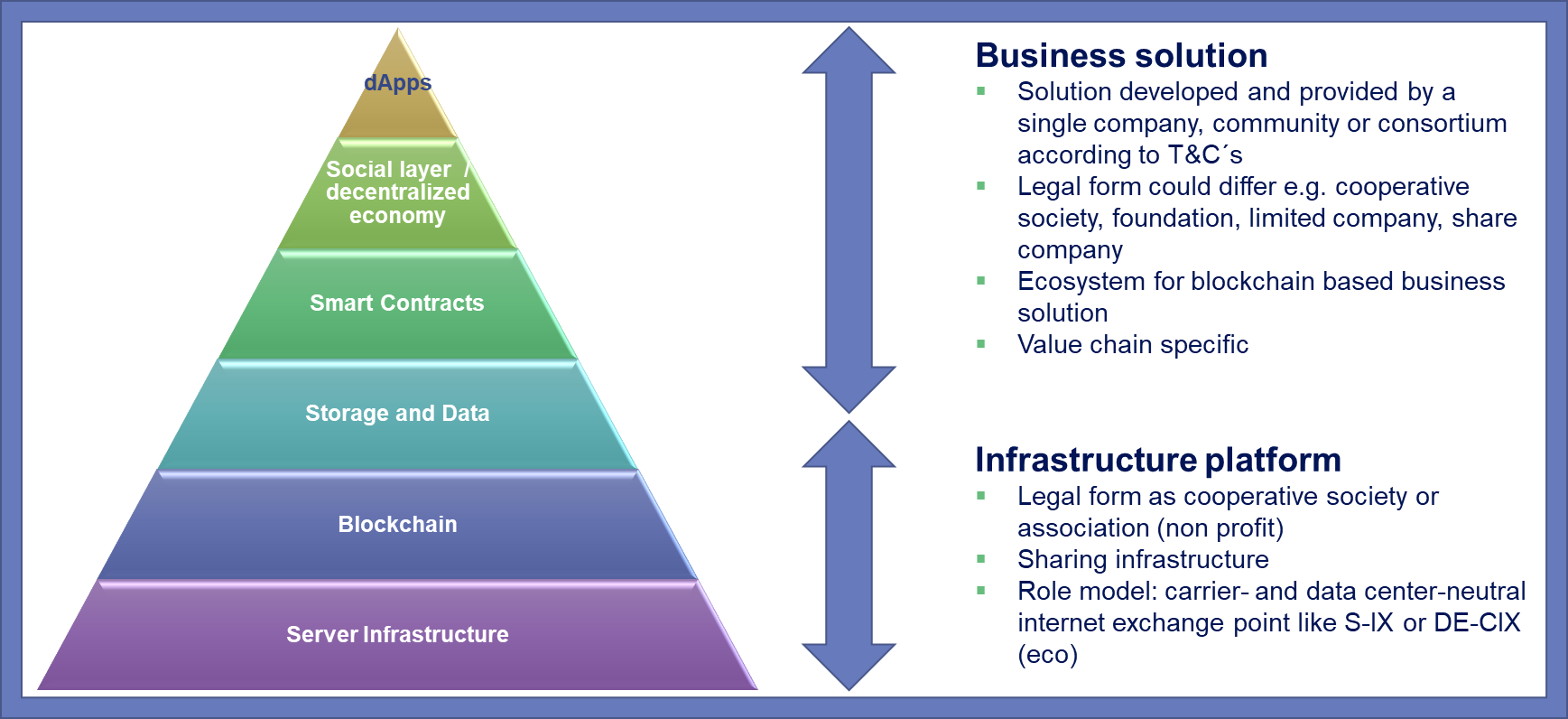

Depending on the situation the different interests of all participants could be outbalanced by splitting the responsibility for the solution in two parts, an infrastructure or platform part and a business solution part.

Figure 3: Splitting the responsibility in a Consortium Chain: infrastructure part and a business solution

The dominant idea for the infrastructure platform part, including the server infrastructure, blockchain protocol and parts of the data layer, would be to share the infrastructure. Thus, a cooperative society or a non-profit association could be an adequate legal form. The later one is, for example, already the chosen form of the internet exchange points S-IX or DE-CIX.

On the other hand, the paradigm for the blockchain solution part could follow the business benefits. An adequate legal form could differ in accordance to the business solution. For example, a data driven business solution covering the entire value chain of a branch could be could be provided of a cooperative society consisting of all participants providing data and benefiting of its analysis. The IP could be owned of the society and licensed to its associates.

IV. Data property as key

As well, data property is a key element of data driven business models. It is essential that to clarify who has the ownership of the data and the results generated based upon it.

Although there is much talk of data ownership, in German and European law the legal concept of data ownership does not exist as an absolute right vis-à-vis everyone.

Within the German Civil Code (BGB), the concept of data ownership is unknown. Property is always related to physical objects (§§ 903, 90 BGB), thus e.g. at the data medium, but not at the data contained on it. Nor can the property law provisions of the German Civil Code be applied analogously, as there is no loophole in the provisions that is contrary to plan. Finally, the legislator has so far deliberately renounced the postulate of data ownership.

The German copyright law protects only the database itself and not parts of its content. According to § 87a German Copyright Act (UrhG)

“a database is a collection of works, data or other independent elements which are systematically or methodically arranged and individually accessible by electronic means or otherwise and the acquisition, verification or presentation of which requires a substantial investment in terms of nature or quantity. A database which has been substantially modified in terms of its content, type or extent, shall be deemed to be a new database if the modification requires a substantial investment in terms of type or extent.”

A database producer within the meaning of the German Copyright Act is the person who made the investment within the meaning the arrangement and/or accessibility. The investment in gathering the data itself or parts of it are not protected.

Although certain business secrets are protected by Act against Unfair Commercial Practices (UWG), data with is on a trade secret such as measurement data or big data analyses in general are not protected. In § 17 UWG only covers cases of betrayal of secrets by an employee, industrial espionage or the exploitation of secrets by unauthorised persons are covered. In particular, the cases in which information is voluntarily entrusted to third parties are not included. Also machine data is only rarely a trade secret. § 18 UWG only protects technical documents and regulations. Only very specific information and, for example, measurement data and big data analyses are protected.

The protection under criminal law applies only if anyone illegally deletes, suppresses, makes unusable or changes data. There is as well, a responsibility for claims for damages and injunctive relief (§§ 823, 1004 BGB) if the access to, or the intervention in the data of a company represents a targeted intervention in the business operations of the company.

Finally, at European level, the GDPR applies to direct or indirect personal data and provides for special rights for the persons concerned, such as objection, information and deletion claims. As a rule, however, machine data are not included, as they are neither direct nor indirect personal data.

As a result of the current situation, data-driven companies should avoid the uncertainty of a non-transparent legal situation and mitigate their legal risks by entering into contracts with data providers.

II. Resume

In summary, sustainable data-driven business models for the Internet of Things (IoT) should not be only technology driven. Start-ups and other companies should think ahead and incorporate robust patterns into their solutions in order to comply with the relevant regulatory framework according to the market addressed.

An appropriate legal form will already be an important step to bring a successful solution to the market. They could also consider entering into watertight contracts with data providers to minimize their legal risks from uncertainty about data ownership.

The Author

Kristian Borkert is the founder of the law firm JURIBO Legal & Consulting. His mission is to simplify digital value creation and enhance its security. His focus is on agile matters, blockchain and IT sourcing.

For almost 10 years Kristian Borkert is working in national and international projects related to information technology and data protection law. His expertise areas include IT and business process outsourcing, SLA, software licensing, software project agreements, data protection agreements and other IT sourcing related topics.

He is particularly interested in agile methods such as Scrum or Kanban, collaboration models and blockchain. He is an active member of blockLAB Stuttgart, Co-Author of the Blockchain Strategy for Baden Württemberg and Co-Creator of the Blockchain Compass.